Sachin Tendulkar is a reservoir of peace, focus and determination

THE guy walking across the parking lot is famous. That’s easy to tell from the reactions. Crowds part for him. Security guards mirror his every step.

Other cricketers who made this same trip to the locker room tiptoed around the puddles.

He strides over them, head up, confident.

I am following an Indian cricket superstar, but I don’t know who he is. That’s the kind of trip this is going to be – one of constant confusion and mystery.

He’s not a big man, but he’s got a big aura. Fans climb the stadium wall, cheek to cheek, pressed against openings to catch a glimpse.

The player looks up at the apartment buildings crowding the other side of the street, like a zoo animal in reverse, all the residents leaning over to get a peek.

He waves his bat at the kids on the wall. The kids scream with joy.

I grab a photographer and point. Who is that?

He looks at me like I’ve got three heads.

Sachin Tendulkar

Oh.

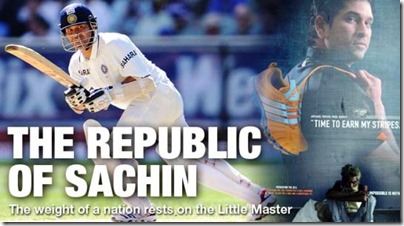

Sachin is both the riddle and the answer. That’s what I’m told. You must understand India to understand Sachin, but you must understand Sachin to understand India. They created each other. They are the same.

This, obviously, makes no sense to me.

How could it? Just a few hours ago I landed in Dhaka from the US. I came with a copy of “Cricket for Dummies’’.

Tendulkar is probably the most famous man in India. He’s so famous that the people who worked for him are famous: a well-known Bollywood movie character is based on his first agent, Mark Mascarenhas, who died in a car wreck.

Billboards with Sachin’s photo blanket India’s cities; every other commercial on television features his face. He’s wildly rich.

He is the greatest cricketer in the world. One of the greatest ever.

I know none of that. At the moment, I’m too busy trying to figure out the definition of a wicket.

Is it the manicured area in the centre of the field? Is it the stumps on either end of that manicured area? Is it when a player gets out?

Cricket, like India, had long intrigued me from afar. It seemed so mysterious: a game with strange rules, and stranger vocabulary; one that can last for days, captivating billions but meriting only a centimetre or two in the papers at home.

Only madness made it to my radar. Fan hangs himself after India loss . . . Pakistan’s coach allegedly murdered

after upset defeat.

Game day outside the stadium is wild. People fill the streets for blocks.

A drum beats somewhere in the distance. Vuvuzelas are the horn section. The roar of the mob gets louder and louder until it’s just white noise. Chaos is the new normal. Loud is the new quiet.

Dhaka, as a city, has ceased to function.

I’m trying to follow the game. I know Tendulkar is a star, so I focus on him. I cannot tell what makes him special. Then, before I know it, he’s out, finished for the day. I don’t really understand why. The fans rise to their feet as he walks off. He’s scored 28 runs.

It all happened so fast. I feel cheated.

The obsession

The next stop in trying to understand cricket is New Delhi. My cab driver’s name is Deepchand Yadav.

He loves cricket. Once, the captain of India’s 1983 World Cup champion team, Kapil Dev, rode in his car. Can

you imagine?! Kapil Dev, in my cab!

Deepchand moved to Delhi from his village 18 years ago. Yadav is a caste name. His caste members are traditionally cow herders, and as India has changed, they have spread through the nation, taking any job they can get, sending money back to the villages.

He is part of post-caste India. Anything is possible through hard work. He grinds, trying to hang on to the first rung of a lower-middle-class life. He’s a smart guy, with a big smile and a luxurious moustache.

His son is 10 years old. The boy plays cricket with friends in the street, wherever they can find a little space, five or six sharing a bat.

The wheels turn.

I ask Deepchand if I could play with them tomorrow. I have watched cricket, but I have never held a bat or struck a ball. Books can take you only so far. The best way to know a sport is to play it with children.

“What’s your son’s name?’’ I ask. “Sachin,’’ he says. Deepchand chose this name carefully.

A name is very important in Hindu culture. The right one, it is believed, can lead a child to immortality. A name is a compass. It points a person in a specific direction.

Of his three children, Deepchand got to name two of them. The girl he called Sonia, after Sonia Gandhi, a politician, “an honest and powerful woman.’’

Deepchand wants his girl to be like her.

He wants his son to be like Sachin: strong, sincere, poised. Sachin represents so many things for Indians who aspire to a better future while not losing their past in the exchange. The name literally means “pure’’.

“He never behaves badly, which Indians find very appealing. He’s not had scandals with women or drugs. He’s the idol for our children,’’ says Rahul Bhattacharya, once a popular young writer on cricket, now a novelist.

Indian legend Sunil Gavaskar, who retired two years before Sachin made his Test debut, seemed terribly insecure. After he became famous, he turned down a membership to London’s exclusive MCC because, once, a guard there didn’t recognise him. The slights burned until they became part of him, his pilot light, defining both him and the nation he represented.

Sachin Tendulkar isn’t from that India.

His international debut came a year before India opened up its economy. His rise mirrored India’s early-1990s rise, when foreign corporations arrived for the first time, accounts swelling with advertising dollars, looking around for a face.

They found Sachin. He was India’s first modern sports star, and he forever changed sports celebrity and marketing in India.

Sachin has been a star since he was a boy. Cops had to stand guard outside his 12th-grade exams. Despite the attention, he has remained dignified. There are no porn stars. He grants few audiences.

He is also the man Indians count on when things are at their worst.

Two weeks after the Mumbai terrorist attacks, with the country reeling, India played a Test match against England and he scored a century, which he dedicated to those suffering in his home town.

Now his career is nearing its end, and fans are left with beautiful memories, to be sure, but also questions.

What does Sachin’s retirement mean for cricket? What does it mean for India?

The legacy

As Sachin grew up watching Sunil Gavaskar, Virender Sehwag grew up watching Sachin. He took what he saw, internalised it and spat out something new, something dangerous, even.

We drive toward the airport, past the endless storefronts featuring posters of bodybuilders. Strength is in.

Out on the edges of Delhi, huge apartment buildings stretch to the horizon. Ugly concrete boxes, row after row of them. If Bruce Springsteen were from India, he would sing about these streets.

There are things being built here. There are things being torn down. A shepherd drives a flock of sheep down the road, moving them into a weedy lot, the proposed site of a cultural centre. He wears a red turban, carries a staff.

Virender Sehwag grew up in these badlands.

He saw Sachin through the prism of the gritty world around him, looking past the grace to the power.

Before Sehwag, Indian opening batsmen were supposed to take the shine off the ball. That’s the cricket phrase. Wear down the bowler. Sehwag would take the shine off by hitting fours and sixes.

And if Sachin gave birth to Sehwag, then a whole group of younger batsmen have taken it a step further. At least Sehwag still plays Test cricket. Some of India’s newer stars don’t.

The Indian team is a blunt object, 15 men created not in the image of Tendulkar, exactly, but in the image of the new India that he both inspired and represented. The players are celebrities now.

We turn on Najafgarh Road. Shop workers give us directions.

In the midst of this urban blight, there is a single planted field. This all used to be farmland. Now there are big piles of sand, the dust of something old waiting to become something new.

White smoke rises from burning trash. Mechanics fixing motorcycles on the sidewalk tell us to take a right at the feeble old tree past the shrine to the monkey god.

This is Sehwag’s street.

When his father died, the neighbours tell us, he moved his mother to a nice place in central Delhi. Other family members live in the house now. There, they point. That’s his aunt. The home is down an alley, where Sehwag used to pound cricket balls.

“He was always a long hitter,’’ a man says.

The house has a big black gate and a bamboo fence to offer privacy for the patio. There’s an orange lantern and a rooftop terrace. It’s the middle-class home that Deepchand dreams of for his family.

This is the home of a grain merchant who moved to the city from a village, wanting to build a new life. Sachin is the son of a poet. Sehwag is the son of man who sold wheat and rice.

The religion

The morning of the India-England match, I wake up anxious. Somehow, on a lark to be introduced to a new sport, I’ve stumbled into a rapidly changing world.

The driver drops me at the main gate and I walk around for several hours.

The air smells like fried food. Vendors sell Indian snacks and sugarcane juice. Cops, wary of another cricket riot, whack sticks against trees whenever someone stops.

We hear the cheers as the Indian bus gets closer.

The soldier on the tower with the rifle stands up from his red chair. Radios squawk. The bus pulls to a stop. Submachine-gun-toting troops in tight T-shirts and khaki fatigues form a wall of flesh and metal.

Sachin Tendulkar is third off the bus.

I recognise him now. We enter the stadium behind the team and the place simmers with anticipation.

Sachin’s name is lost in the cheers. The crowd roars even in anticipation of it. Once again, Sachin walks on to the field, and Sehwag is with him.

A feeling arises, a rare one, that you are part of a group watching something special. The power of sport is that, on occasion, it redeems the messes we create around it. Cricket can be stronger than the forces changing it. Victories are fleeting, but the poems are what matters.

We are congregants in a church. We are watching the son of a poet.

Sachin is building toward a century. He gets to 98. He hits a four. The place erupts.

I’ve never been in a stadium that feels like this one. Hindus and Muslims, Sikhs and Christians, people from different castes and classes, speakers of a dozen languages, all citizens in the Republic of Sachin.

There is one last stop that remains before the airport.

“We’ve got 30 seconds,’’ his agent says.

A special key card grants access to the 18th floor. Three plainclothes bodyguards look us over. A sign hangs on the door. “Shhh,’’ it reads, “I’m sleeping like a baby.’’

The agent knocks.

Sachin Tendulkar opens the door. “Come, come,’’ he says.

A tangle of wires covers the bedside table closest to his pillow. There’s a Diet Coke and a bottle of water. A Hindu shrine is on the other side.

There’s a book across the room, The Last Nizam, about the end of one era and the beginning of another, about a king who lost his throne in a time of great change.

His agent explains my journey to Sachin. “He didn’t know anything about cricket before he came,’’ he says.

Sachin looks at me. He seems confused. “Hmmmmm,’’ he says. His phone rings. The ringtone is U2. We chat,

and he loosens.

He doesn’t overtalk. It’s strange. There is an aura of calm around him. It must be how he’s survived. At the centre of this mania is a reservoir of peace, focus and determination.

He’s carried the burden of a billion people for more than 20 years. His agent told me he’s aware of what he means to people, of the symbolic importance of being both the beginning and end of something.

In his room, he seems tired, worn out mentally and physically. He needs a break. I ask when was the last time he had 20 days off in a row with nothing to do. No balls to hit or billions to represent. “I’m waiting for that time to come,’’ he says.

© HERALDSUN